SPOILERS AHEAD: Given my initial apprehensions about Apple TV’s adaptation of Foundation, and my many readings of Asimov’s series of the years, I couldn’t find a way to write this post without including spoilers both to the two episodes that have appeared thus far, and to the books. If you have not yet watched the first two episodes of Apple TV’s Foundation, or have not read the Foundation novels and plan to either, be warned: spoilers to both lie here within.

This past Friday, I sat down to watch the first two episodes of Apple TV’s production of Isaac Asimov’s Foundation. If you are here to find out if my apprehensions were well-founded, or if I liked what I saw, and want to avoid any spoilers, read no further than the next three sentences: I loved it. I was surprised by how much I enjoyed it. Indeed, I enjoyed it so much I watched it a second time on Sunday.

To understand why I enjoyed it as much as I did requires knowing something about the Foundation stories, and that is why spoilers are required. If you are not interested in anything more than whether or not I liked it, you have the answer now, and can stop reading. Thanks for stopping by. If you are curious as to why I think it so good, thus far, read on, but be warned, spoilers follow.

1. Understand that this is an adaptation

I went into this with the clear recognition that this was an adaptation of Asimov’s work. Adaptations, at least good ones, are not meant to be strict copies of the original canon. They bring to bear the views and artistic insights of those involved in adapting the story. Some adaptations are bad: the 2004 adaptation of Isaac Asimov’s I. Robot is one example, in my opinion. There was very little of the heart of the robot stories in that movie. A good adaptation maintains the heart of the original and builds upon it. Think of The Shawshank Redemption. It is an outstanding adaptation to an outstanding story, but it is not an exact copy. There are important changes that make it different, interesting, and yet you can see the core there, and how it was built upon.

The core is there in Apple TV’s Foundation. Almost from the outset, we hear the names “Salvor Hardin”, “Hober Mallow”, and “the Mule.” We hear them in the voice of Gaal Dornick, who in addition to playing a pivotal role in the story, acts as the episodes’ narrator. And even that stays true to the original stories. In “The Encyclopedists,” written in 1950 as a kind of prequel to the original Foundation stories (which themselves were written in the 1940s), we are told:

…the best existing authority we have for the details of [Hari Seldon’s] life is the biography written by Gaal Dornick, who, as a young man, met Seldon two years before the great mathematician’s death.

2. Depth and background has been added to the story

But Gaal Dornick is not a young man in the Apple TV adaptation; she is a young woman and one with an interesting background. This is an example of the depth and background that as been added to the story in the adaptation.

Isaac Asimov wrote about ideas. He wasn’t much for backstory, and where it existed in his original Foundation stories, it was there to further the ideas about which he wrote. Readers have often complained, for instance, that many of Asimov’s stories, including the early Foundation stories, completely lacked women. Asimov argued that at the time he wrote these stories (he was 21 when he started the first Foundation story) he had no experience with women. That is a flaw in the Foundation stories that he attempts to correct in some of the later stories.

In Apple TV’s Foundation, the adaptation faces this head-on. Gaal Dornick is woman. Salvor Hardin is a woman. And perhaps best of all, Eto Demerzel is a woman.

I loved the backstory given to Gaal Dornick, and I liked the idea of the triumvirate of Dawn, Day, and Dusk, that make up the cloned descendants of Cleon I who rule the empire. These are details that breathe life into characters originally written to serve ideas in the story, rather than be living, breathing people in their own right.

Raych is another character that has been introduced early, and here, things are more subtle, because Raych was fleshed somewhat in the latter Foundation novels in the 1980s. We know in the Apple TV adaptation that Raych is Hari Seldon’s son, but we know he is his adopted son. We don’t know much more than that.

3. Moving through time

Gaal Dornick narrates the story, and we see that story move between the “present” time, when the Foundation is on Terminus, 35 years after the trial of Hari Seldon. We see the mysterious Vault, and the kids who try to make it as far into the null field that surrounds the vault as they can, to plant their flag. We learn that Salvor Hardin, the “Warden” has made it the farthest of anyone, that she doesn’t seem to be affected by the null field. We don’t know what the null field is, or why it is there, or what it is hiding in the vault, other than rumors of a ghost.

Of course, if you’ve read the books, you have a good idea of what is going on here. The null field is a kind of mental barrier that can’t be passed by most people. And there is only one group who could create such a mental barrier. I’ll come to that a bit later.

The episodes set up short segments on Terminus in the present, and then flash back 35 years to the time when Hari Seldon’s predictions are revealed to the galaxy during his trial.

Once again, the heart of the Foundation stories are preserved here. The trial of Hari Seldon differs mainly in that Gaal Dornick is also on trial, and that she is there to verify his claims. A line from the original remains in the script, when the advocate in the trial presses Seldon on the fact that the empire has been around for 12,000 years and seems as strong as ever. In the book, Seldon says, “The rotten tree-trunk, until the very moment when the storm-blast breaks it in two, has all the appearance of strength it ever had,” The Hari Seldon on screen in the adaptation says something very similar.

4. The core story is being told in the best way possible for the medium

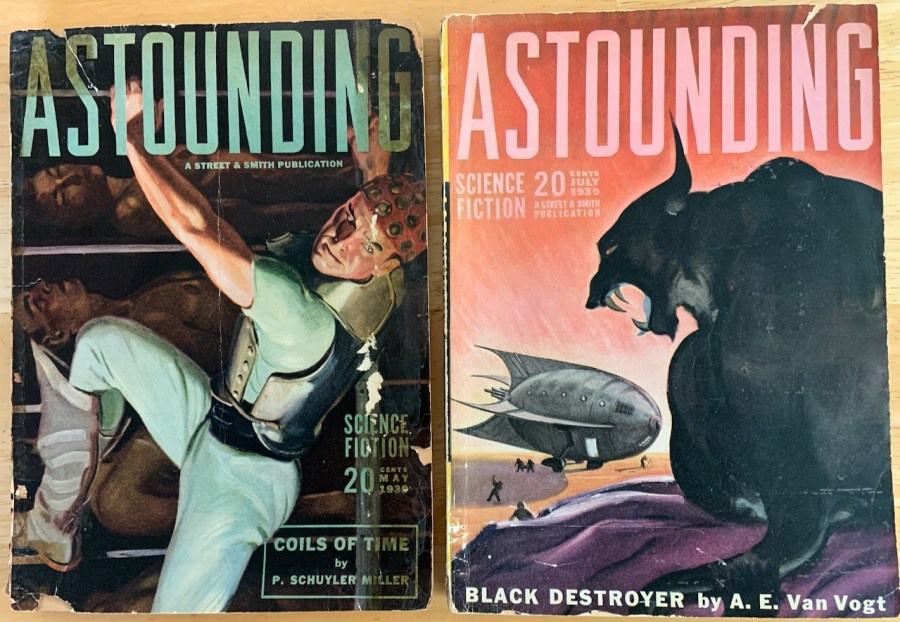

Isaac Asimov had no idea where the stories where going when he wrote them. Remember, that the original Foundation trilogy was a collection of stories that originally appeared in Astounding Science Fiction in the 1940s. Asimov wrote the first without any idea of what would happen next. John W. Campbell, editor of Astounding, tried to convince Asimov to produce an outline of the future history of the Galactic Empire, in much the same way Robert A. Heinlein had produced an outline for his Future History stories, but Asimov refused. That wasn’t how he worked.

Those adapting the story had an advantage that Asimov never had: they knew the entire story before they ever started out. And it was clear to me that they planned to take full advantage of that fact.

Serious spoilers ahead, so take heed.

I was delighted to see Eto Demerzel show up early in the first episode. Demerzel was introduced in the Foundation stories late in the game, in Prelude to Foundation, published in the late 1980s. If the Galactic Empire has been around for 12,000 years, well, guess what, Demerzel has been around longer. She has used different names, and appeared under different guises (including male guises) because Eto Demerzel is robot. We get hints of this in the second episode, when Dawn watches her repair herself from an injury she sustained.

She is not just any robot, however, she is a robot named R. Daniel Olivaw, who made is first appearance in Isaac Asimov’s The Caves of Steel. While she appears as the Empire’s advisor, she is an ally of Hari Seldon and his cause.

Hari Seldon always intended for the Foundation to be established with imperial support, but away from the eyes of the empire. He used his predictive science of psychohistory to try to get the Foundation established on Terminus–and his plan succeeded. But there is a question that no one has yet asked: his science is predictive; how then, did he manipulate events in his favor?

There is a scene in the first episode that gives a clue. On her journey from Synnax to Trantor, Gaal experience the Jump–that passage through hyperspace that allows a galaxy-spanning empire to exist in the first place. Passengers are put to sleep during the jump because, as the spy Jerill says, “Your mind might separate from your body.” Except that Gaal awakens during the sleep and sees the passage. One of the Spacers asks, “How can you be awake?” and then puts her back out. What is it that makes Gaal different?

Toward the end of the first episode, we get a second hint. Just before terrorists blow up the star bridge, Gaal looks up to the sky and tells Hari that the sky is not right, that there is something wrong with the bridge. How did she know before it happened?

The answers to these question, I suspect, lie with the idea that the adaptation has been created with full knowledge of the events of the Foundation stories, and advantage Asimov did not have when he wrote them.

Consider: in the books, Hari Seldon never goes to Terminus. He has other business to attend to. In the adaptation, he goes with the team to Termius in the slow-ship, so that the journey takes over 5 years to get there. But, as we discover toward the end of the second episode, Seldon apparently dies–is killed, it would seem, and Raych, puts Gaal Dornick in an escape pod and launches her into space. It seems that with Seldon seemingly dead and Gaal gone, we are back on track.

I believe this is the writers attempt to setup the bigger reveal: Seldon, along with Gaal and likely with the help of Demerzel, return to Trantor to establish the second Foundation. The second Foundation is the secret Foundation. It is the one that must work in secret for it is the one that can manipulate history through subtle mental abilities that can influence people’s behavior. I suspect that Gaal’s waking up during the Jump, and her knowing there was something wrong with the star bridge before anything happened were clues that she was someone with this mental ability. At one point she says, “I could feel the Empire’s fear.” At another point, in the library after meeting with Gaal, Raych asks Hari for his impressions: “She solved Abraxis, of that I’m sure,” Seldon said, “As for the other thing…”

This mental ability is “the other thing” to which Seldon is referring.

5. Exciting possibilities

All of this makes for exciting possibilities. I can see the future episodes being split between the establishment of the first Foundation on Terminus, and the struggles they go through as they grow, develop, and begin to handle each of the “Seldon Crises” that arise in order to help minimize the duration of the Dark Ages. At the same time, with Seldon and Dornick back on Trantor, we have not only a view of the establishment of the Second Foundation, their secret role, but also a direct view into he fall of the Empire. This makes the most sense to me and it makes for dramatic episodic televisions as well.

6. Sense of wonder

After I watched the first two episodes of Foundation, I couldn’t get it out of my head. I kept thinking about it. It was a visual marvel. And what occurred to me is that I was seeing much of what I imagined when I first read the books. Gaal’s reaction to Trantor was my own. I never questioned it, and it felt like what I was seeing was the Trantor I had always imagined. The feeling lingered, and just before I decided to watch the two episodes a second time, I realized what that feeling was: it was the sense of wonder that attracted me to science fiction in the first place. It has been a long time since I’d felt that sense of wonder. The fact that Apple TV’s adaptation of Foundation could generate that sense of wonder within me probably explains, to a large extent, why I loved the first two episodes so much.

Did you enjoy this post?

If so, consider subscribing to the blog using the form below or clicking on the button below to follow the blog. And consider telling a friend about it. Already a reader or subscriber to the blog? Thanks for reading!

Follow Jamie Todd Rubin on WordPress.com

Like this:

Like Loading...

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts