Welcome to my blog series, “Practically Paperless with Obsidian.” Foran overview of this series, please see Episode 0: Series Overview.

Nearly 10 years ago, I began an experiment to see if the elusive paperless office was actually possible. That series, Going Paperless, was my attempt to use Evernote and other tools to go completely paperless. After several years, my conclusion was that it was not really possible for me to go completely paperless. In the years since, I’ve returned to paper for several things, but still enjoy the efficiencies of having information I need at my fingertips. In examining the lessons I learned from my paperless experiment, I realized that, as with most things, moderation is key. There is a difference between going completely paperless, and looking to be paperless in the practical sense. That is what this series is all about.

Instead of Evernote, I’ve decided to use Obsidian instead. I’ve written about why I want to use Obsidian elsewhere, but the gist of it is:

- files are plain text, which makes them essentially future-proof;

- files are stored locally instead of on someone else’s server (unless you want to store your files in a cloud system like iCloud, Dropbox, OneDrive, etc.);

- it has a great note-linking function that I will make heavy use of as we progress through this series.

Of course, if you are following along, you don’t have to use Obsidian. Evernote still works for much of what I’ll be discussing. If you are not going to use Obsidian, you can safely skip the first three episodes of this series, as they focus on setting a kind of baseline with the tool for moving forward through subsequent episodes.

The first 20 episodes in this series build upon one another. I am using them as a guidepost for getting me to where I want to be. The first 3 episodes establish some basics, beginning here with how I plan on storing my notes. A note can be anything, text, a document, and image. When I think about what I want to be able to capture in digital form, I think of notes in two categories: notes and documents.

Notes in Obsidian

A note is just a markdown file (.md) file in Obsidian. Markdown, for those not familiar, is a plain text file in which special markup can be used to format the note. This is light markup, not as elaborate as, say HTML. In a plain-text markdown file, for instance, if I want to bold some text, I surround it with a double asterisk **like this**.

For me, notes are distinguished from documents in that a note is a markdown file. A document is something else, like a PDF or an image file. I’ll discuss those files in a moment. Notes can be viewed in two ways within Obsidian. They can be viewed in edit mode, where you can see the markup’s that you add to the note; and they can be viewed in Preview mode, which renders the notes fully formatted. Here is an example the same note rendered in edit mode and preview mode in Obsidian. You can use the slider bar to see how they look different.

Notes are where the majority of my paperless stuff goes. The note in the example above is from my “commonplace” notebook, a collection of notes and highlights from my reading. At its most basic, a note in Obsidian is a file on your file system. The note has title1, and it has the same file attributes as any file on your file system: create date, modified date, permissions, etc. I’ll have more to say about note titles in Episode 6.

Obsidian uses the concept of a “vault” to store notes. A vault is nothing more than a folder on your computer. Obsidian controls and monitors the files and folders within that vault folder. This is incredibly useful. It means that you can move notes around within your vault and Obsidian will take care of maintaining the links that notes have to other notes automatically.

Note-linking is a key reason why I love Obsidian and I’ll have a lot more to say on it in Episodes 17 and 19. For now, note links are simply links to other notes in your vault. In the example above, the “[[202109220957 Natural Questions]] on the “source” line is an example of a note link. Clicking on the link takes you to that note.

Just like in Evernote, notes can have tags. Obsidian uses the hashtag format for tags. In the example above, you can see two tags: #discovery and #favorite. One difference between tags in Obsidian and Evernote is you can refer to tags anywhere in a note in Obsidian. And because Obsidian’s search capabilities are very granular, that means that sections or even lines of a note can appear in search results, making tags quite powerful. I’ll have more to say about tagging in Episodes 7-10.

Notes, then, are containers for information you want to capture. They are the basic unit of storage in Obsidian. You can create notes quickly with a hot key and start typing. Obsidian saves as you type so you don’t have to worry about remembering to click a Save button.

Notes have one other very powerful feature in Obsidian that they lack in Evernote: transclusion. Transclusion allows you to include a note within another note. When I read, I highlight passages, and those passages, after I review them, each get their own note in Obsidian. Here is an example from when I was reading Franklin D. Roosevelt: A Political Life by Robert Dallek:

For books with notes, I keep a “source” note to collect all of the notes related to that book together, as well as any other thoughts I might have about the book not captured in a specific note. Rather than have to copy and paste the notes into the source note, I can “transclude” the note into the source instead, thus reusing the existing note, almost as if it were a subroutine. Here is my source note for the book in Edit mode:

In the “Notes” section, note that all I did was include links to my notes on the books. Note the ! that precedes each note link? That is what tells Obsidian to transclude the note in Preview mode. So when I look at this note in Preview mode, what I see is:

Each of the two note links are transcluded–they include the entire note–within the note in which they are references. This turns out to be incredibly useful with documents.

Documents in Obsidian

I think of a document as something other than a note. Much of what I collected in Evernote over the years were scanned PDFs, or PDFs automatically sent to Evernote through a service like FileThis. Think: bank statements, tax forms, official documents, instructions for household appliances, etc.

Obsidian has the ability to keep track of and render certain types of documents files, among them PDFs and image files. You have the ability to store these files right along with your notes, or you can separate them out into their own folders in a number of different ways. I’ll have more to say on this in Episode 2.

In order to keep things simple, I created a folder called “_attachments” in which any and all document files go. This includes PDFs, image files, and any other files that fit this category. The reason for this is that I don’t just use the bare attachment file, but I couple it with a note in order to gain the benefit of all of the Obsidian functionality that comes with notes. Let me give an example.

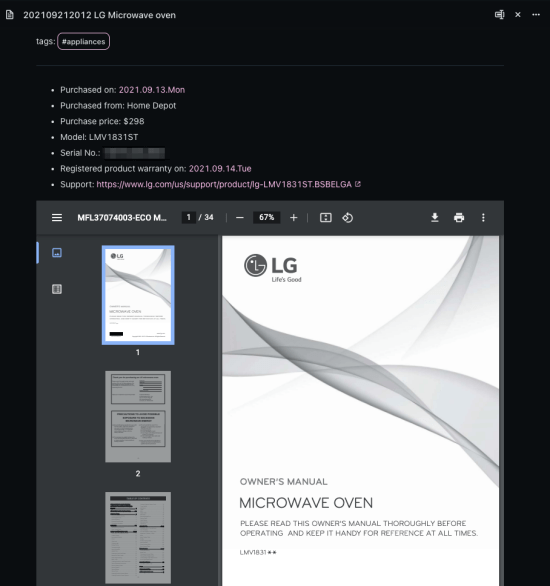

We recently got a new microwave oven, which I ended up installing myself. Information about electronics and appliances is something that I actually use from time-to-time, and just as I did in Evernote, I created a note for the new microwave in Obsidian.

I use a similar format for all electronics and furniture because it means I have one centralized place to go for anything related to that thing. Obsidian has the ability to create templates for notes, similar to Evernote. I’ll discuss this in more detail in Episode 8. The “Timeline” section is a running timeline of events related to the microwave. If, for instance, I had to call for support, I’d add an entry to the timeline to record information about that call to support. All of the information I need is right there and easy to locate.

Note that there is a translcuded note link for the Owner’s Manual PDF file. I put the PDF file in my “_attachments” folder, but I don’t have to worry about where it is. When I go to add the link, I just start typing and Obsidian presents me with a list of matches anywhere in my vault. Because it is a transcluded note link, when I look at this note in Preview mode, what I see is:

I have the ability to scroll through the pages of the PDF, or print the PDF if I want to. It’s all right there, included as part of the note on the new microwave oven. Many notes are just the document itself, so the note will contain nothing but a title, some tags, and then a transcluded link to the actual note, say a bank statement or tax form. This gives the added benefit of searching the meta-data in the note to find what I am looking for. I’ll illustrate more examples of this when I talk about finding note in Episodes 15-17.

Notes are just files in the filesystem

I want to stress the point that these note are just files in my file system. This is a big difference from Evernote, which stored notes as objects on their server, which could be downloaded to your client. Here is a look at what my vault in Obsidian looks like (on the left) and a similar look at what this looks like on my filesystem (on the right):

The “DFC” is the name I gave my vault in Obsidian. It stand for “Digital Filing Cabinet.” I can open any of these notes outside of Obsidian in a text editor and still be able to read and use (and even update) the note. For instance, opening the microwave note looks as follows on my Mac’s TextEdit app:

Establishing a baseline

I wanted to begin this series with something simple, illustrating how notes are captured in Obsidian, because I wanted to establish a baseline. I wanted to give people who are used to using a tool like Evernote or OneNote an idea of how their notes might be stored in a tool that is essentially a fancy text editor. To that end, I identified two types of notes that I capture–notes and documents–and showed how I am using these separately and in combination to capture notes in Obsidian similar to how I captured them in Evernote. I was trying to answer the question: what would my notes look like in Obsidian?

Again, as I attempt to go practically paperless, I’m using Obsidian because it is simple, future-proof, and doesn’t require paying for cloud service if you don’t want one. Documents are stored locally and because they are plain text files with some PDFs and images in the mix, you can use your OS to manage the files, and even search the files. Running a Spotlight search for “LG Microwave” on my Mac instantly returns the following:

But I like Obsidian because of its note-linking capability, as well as its ability to manage the vault, keeping links updated even as I move notes around in the vault. It also has some powerful search capabilities that even Evernote lacks (like regular expression searches). And it provides an interface that separates my notes from other things that I do. This series will focus on using Obsidian as I attempt to go practically paperless, but I hope it is clear that other tools can work as well. This just happens to be the one that I think is best suited for this task.

Next week: Continuing down the path of establishing the basics for this experiment, next week will focus on Obsidian and how I have configured it to take advantage of features and plug-ins that I think are most useful for managing my notes. A week later, in Episode 3, I’ll show how I emulate some of Evernote’s useful features in Obsidian.

Next: Episode 2: The Basics: My Obsidian Configuration

Did you enjoy this post?

If so, consider subscribing to the blog using the form below or clicking on the button below to follow the blog. And consider telling a friend about it. Already a reader or subscriber to the blog? Thanks for reading!

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

I’m intrigued. This is way beyond my current note taking system, which is a combination of Field Notes and a gigantic word document. I’m gaining an ever growing database of classic movie trivia research for my own blog that I’m trying to find a way to organize. This may end up being beyond what I’m willing to maintain, but I might give it a shot. Gonna read the next few episodes before I decide one way or another.

Now off to google Obsidian and markdown…….

Melanie, one worry I had about this initial post is that I am making it look more complicated than it is, in order to explain how notes and documents can be captured in essentially plain text files. I actually think that this is an almost idea system for a database of film trivia, especially with the note-linking ability. You could have a note for each film and a separate note for each actor, director, etc., and easily link notes together, and then view the graph of the links between notes and find all kinds of unexpected and interesting associations. In Epsiode 3, I should have some examples that compare creating and editing notes in Obsidian with Evernote and that should make things more clear than what I have here (I hope!).

I can’t wait to read more!

BTW, with all of the fascinating writing you’ve been doing on films, it has to have crossed your mind to turn those posts into a book, right? I think it would be an amazing book.

You know, it’s funny you mention that….I do have an idea in mind and was wondering if I have the guts to pull it off. So this is great to hear such a book would have an audience!

I was actually thinking more of taking one of the stories and expanding into a historical fiction novel.

Great article! I have a couple of questions about the attachments. Can Obsidian accommodate attachment types other than image and pdf? If the pdf has been ocr’d before saving it in the vault is it searchable within Obsidian?

One of the nice things about Obsidian is that there is an amazing community of developers who build plugins for the app. There is a plugin that can extract text from images, and then add the text near the image: https://github.com/schlundd/obsidian-ocr-plugin

I haven’t tried to search for text in a OCR’d PDF myself, though. That would be really interesting.

Paul, I just tried the OCR’d PDF experiment. No joy. (See my previous comment.)

Thanks for the update!

Im using native iOS on iPhone for OCR on pdf’s and images. best thing is that I can search whole disk and cloud for content im looking for. Paired with Obsidian its a monster of a research tool

Michael, on your first question, here are the files types that Obsidian can currently keep track of in the vault. These file types can also be embedded in notes, as I showed with the PDF in the post. On your second question, I tested this out by scanning a PDF with OCR containing a term (“posnanski”) that returned no results in my current vault. After adding the PDF to the vault, it still came up with no matches. However, there is a lot of discussion about adding this feature on the Obsidian discussion boards and I imagine it will come along as a plug-in, if not a native feature, soon enough.

Oh sure… Obsidian can take on all formats of files as attachments. Count in audios, videos, archives(compressed files) and even those that can’t be opened or viewed in the Obsidian.

Thank you for the interesting article series! . . . Reblogged on https://ronrieck.wordpress.com . .